Thomas Rotch (1767-1823)

Thomas was born to Quaker parents, William and Elizabeth Rotch. William was a partner in the firm of Joseph Rotch & Co. (later William Rotch and Sons), with headquarters in Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts and later a branch in Dunkirk, France. The firm engaged in the whaling and shipping industry, and also owned a rope walk and candle factory. Two of the three ships involved in the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773 were owned by William and Francis Rotch (father and uncle of Thomas respectively). The ships were the Beaver and the Dartmouth, loaded with cargoes of tea. The first ship to unfurl the American flag after the Revolution in England was William Rotch’s ship, Bedford, which arrived on the Thames in February 1783.

Today, the warehouse and counting house built in Nantucket in 1775 by William Rotch still stand. The Revolutionary War caused William Rotch considerable financial loss through capture of his ships and interruption of the whaling industry. Although he tried to maintain a strict neutrality in accordance with his Quaker beliefs, many non-Quakers accused him of being a Tory. In 1785 he went first to England, then to France to try to establish whale fisheries there. His son-in-law, Samuel Rodman, was left in charge of the Nantucket interests, and his son, William Jr. in charge of those in New Bedford.

Charity (Rodman) Rotch (1766-1824)

Charity was born in Newport, Rhode Island, on October 31, 1766, the youngest daughter of Thomas and Mary (Borden) Rodman. Her father, a ship captain, was lost at sea when Charity was less than a month old. The Rodman and Rotch families had known each other for some time, for Charity’s oldest brother, Samuel, had married Thomas’s sister, Elizabeth, in 1780, and her sister, Elizabeth, had married Thomas’s brother, William, in 1782. Quakers from all over New England came to Newport to attend the Yearly Meeting, so the two families would have had much opportunity to become acquainted. On May 6, 1790, Thomas Rotch and Charity Rodman were married.

New Bedford, Massachusetts

In 1791, Thomas and Charity moved to New Bedford. Thomas went there to join his brother, William, at the New Bedford branch of the whaling firm. While they lived in New Bedford, Thomas was active in the affairs of the town, serving as Treasurer of the Proprietors of the New Bedford Bridge, and handling the finances connected with building the bridge.

Thomas and Charity had only one child, Thomas (Tomy), was born on July 29, 1791, soon after they moved to New Bedford. Tomy died on November 19th of the same year of quincy, which is a severe form of tonsillitis which was often fatal to children at the time.

Thomas was also active in Quaker affairs, making a long missionary journey to Nova Scotia in 1794. This missionary concern apparently motivated Thomas and Charity to move to Hartford, Connecticut, in October, 1800, for Thomas describes himself as going there primarily as a missionary.

Hartford, Connecticut

In Hartford, Thomas owned a store, a mill for pressing linseed oil, a rolling and slitting mill, and a woolen mill. After Merino sheep were introduced into the U.S. from Spain in 1802 by Col. David Humphrey, Thomas became interested in breeding them for their fine wool. By 1811, he had built up a flock of 408.

Arvine Wales, who had come to work for Thomas, appears to have quickly been put in charge of the Merino sheep, as many of the records pertaining to them are in his handwriting. To view Thomas Rotch and Arvine Wales’ book about Merino sheep, click here to view the Massillon Public Library’s digitized version.

While the Rotches were living in Hartford, Charity developed a illness known as spotted fever, and repeated attacks were making her weaker. Her doctors tried many different remedies. After none of them were successful, it was recommended to them that they move away from New England, to look for a more suitable climate for Charity.

The move to Ohio

Frustrated, Thomas and Charity set out in January of 1811 to look for a place to settle. They had heard of a placed called Ohio, and wanted to see if it would work for them. They crossed the Allegheny Mountains to Pittsburgh, traveled along the Ohio River to Cincinnati, and then northeast between the Great Miami and Little Miami Rivers and over the Pickaway Plains, near where Columbus is. Charity Rotch kept a detailed journal of the trip, which can be read here.

Thomas was looking for good pasture land for his sheep and a site for a woolen mill. While on their journal, Thomas and Charity connected with a man named Bezaleel Wells in Steubenville. Wells was a Quaker, who in 1805, had founded the town of Canton. Bezaleel Wells described the area around Canton, which met Thomas and Charity’s expectations.

Nearby Canton was an area called the Plains of Sippo, which were less densely forested because the Indigenous peoples had cleared the land for hunting. Thomas and Charity realized this would make it easier to plant crops, pasture sheep, and build a settlement. Thomas also liked the waterways, especially Sippo Creek, because it would provide power for his woolen mill. After returning home, Thomas wrapped up any loose ends he had in Hartford and was ready to move by September.

While Thomas was finishing his business, Arvine Wales decided to move to Ohio with them and left in September with six other men to drive the flock of 408 Merino. The journey by foot took them two months. While crossing the Allegheny Mountains in Pennsylvania, they had to improvise leather muzzles and hired three additional men to keep the sheep from eating mountain laurel. On the entire journey, they lost only about ten sheep. Thomas and Charity, coming in a carriage, met Arvine, the nine men, and the 400 sheep near Bedford, Pennsylvania, before the entire party arrived at Steubenville in November.

Charity went to Wheeling to spend the winter with friends there, and Arvine took half the flock to winter at Cross Creek near Steubenville. Thomas and other men proceeded to Sippo with the rest of the flock. They build folds for the sheep and a small log cabin for themselves. A friend wrote to Charity that they had plenty of food and blankets, but the space in the cabin was so limited that there was not enough room for all the men to sleep. Thomas would rig a hammock about five feet off the ground, which he accessed by a rope.

Kendal’s Foundation

Thomas had bought 2,500 acres of land, to which he later added 1,500 acres more. On April 20, 1812, he recorded at Canton the plat for the town of Kendal, with himself listed as proprietor. There were 102 lots in the plat, and the town was laid out on both sides of State Street, which at the time was the main road from Canton.

The streets paralleling State Street were given family names such as Rodman, Elizabeth, and William. Front Street (now Wales Road) was the main north-south street. The other north-south streets were numbered from First to Fifth. Two greens, named Union Square and Charity Square, were laid out adjoining Front Street, which made Kendal look like a New England town.

Courtesy Massillon Museum

In order to encourage industry and make sure that the settlers were responsible citizens, Thomas restricted sale of lots to ‘mechanic and manufacturers’ and stipulated that everyone who bought a lot must build on it within a year. Houses were not permitted to be of logs, but must be of frame, brick, or stone. They had to be at least 16 by 20 feet, a story and a half high, and must have a chimney. The estimated cost at this time for building a frame house to meet these specifications was $85.30, including shingles and 27 panes of window glass. Many of the early settlers were fellow Quakers from Nantucket, who had sufficient funds to meet requirements, but a later resident thought the restrictions kept the village from growing as much as it could have.

Photograph taken by Albert Coleman from the Standpipe near Sippo Reservoir Falls.

Courtesy Massillon Museum

Thomas began operating a store in Kendal almost immediately, and by 1813 a post office had been established with himself as postmaster. A brickyard was also started very soon and by 1816 an imposing two-story brick house had been built on Front Street for Alexander Skinner. By the end of 1816 the town had 40-50 houses, a powder mill, a pottery, two saw mills, a flour mill, and a woolen factory. People brought wool to be made into cloth from as much as fifty miles away. A meeting house was built near the woolen mill, and was later was replaced by a brick one.

Due to Kendal’s success, when the community of Zoar was established in 1817, Thomas acted as a liaison between the Zoarites and Quakers in Philadelphia who had helped them. He reported to the Quakers on the Zoarites’ progress, and forwarded funds collected by the Quakers for the Zoarites.

Thomas built a large log house on the hillside slightly southeast of the present house and he and Charity lived there until the present Spring Hill house was built between 1821 to 1823.

The Underground Railroad

Like many other Quakers, Thomas and Charity were opposed to slavery, and Spring Hill Farm became a station on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers were hidden in the upper story of the Spring House, before moving to other stations. On one occasion Thomas received a letter of gratitude from a freedom seeker named George Duncan. The entire letter is preserved in the archives of the Massillon Public Library. You can view it here. To read more on our Underground Railroad research, click here.

Indigenous Peoples

The Sippo Valley area was used for managed game hunting by the indigenous Delaware people (Lenape). Because the Lenape had cleared the forests to make hunting easier, American settlers found the land easy to cultivate and develop. In response to the settlement of their land, and with British troops encouragement during the War of 1812, the Lenape and other Nations harassed the settlers of Kendal and West Massillon.

Thomas Rotch acted as an intermediary between American settlers and the indigenous people. On one occasion, he was given power of attorney to return a horse that the Lenape believed had been stolen from them. Thomas wrote that he helped out of “fearful apprehension of consequences that are well known to await the families of those that the Indians believe they have just cause to retaliate upon.” He did, however, come to believe that the Lenape were mistaken about the horse, convincing them to let the matter go.

In 1818, Thomas Rotch received 150 pounds sterling from Quakers in Ireland to be used by the Yearly Meeting of Ohio Quakers for the suffering of indigenous people. Thomas, being on the Committee on Indian Affairs, left the meeting with two others, riding across the state to St. Mary’s, Ohio, where a treaty for the purchase of large tracts of land from several indigenous groups was being negotiated. He used the monetary gift as an opportunity to convey to the “most untaught and hostile tribes the Quakers desire to aid and instruct them in the cultivation of their lands and that we desired to live in peace with all Nations.” Thomas reacquainted himself with several chiefs who, to his astonishment, recognized him at first glance, and were well disposed to his offer of agricultural assistance.

Deaths of Thomas and Charity Rotch

In 1823, Thomas was attending the Yearly Meeting in Mt. Pleasant, Ohio, when he became ill with a “bilious fever,” and died unexpectedly on September 14th at the age of 56. As was the custom with Quakers, he was buried in an unmarked grave in the Quaker cemetery at Short Creek, six miles from Mt. Pleasant, Ohio.

Charity died at Spring Hill on August 8, 1824. She is buried in the Quaker cemetery on Seneca Street NE, and though not confirmed, researchers believe her grave is marked with a small sandstone marker bearing the initials “C.R.”

The Rotch Legacy: The Charity School of Kendal

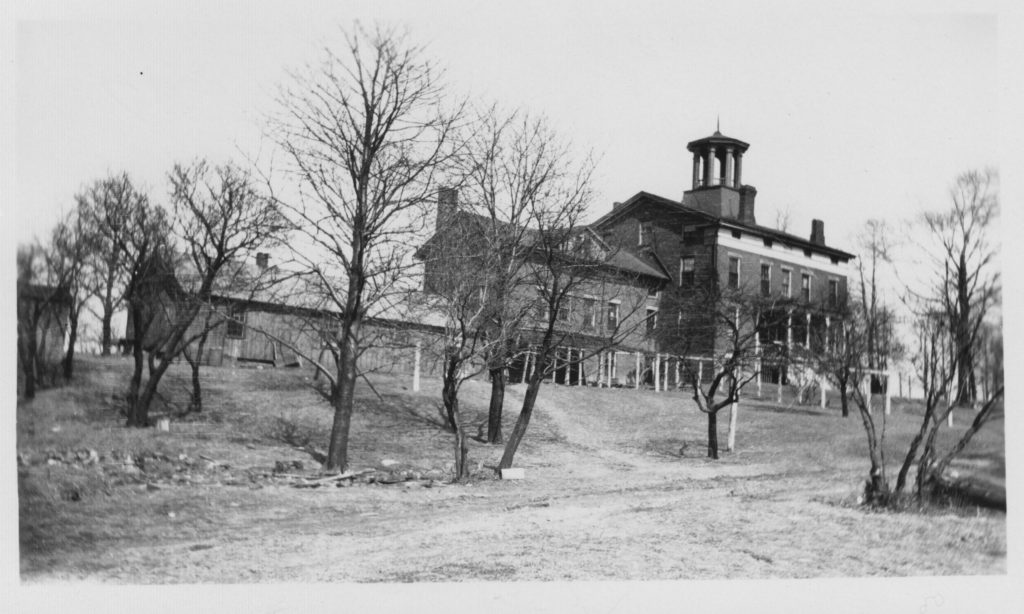

Among her bequests, Charity left funds to establish a school for orphans or children of indigent parents. Twenty children of each sex would be taken for a four-year period, and in addition to receiving a good basic education, the girls would be taught cooking and sewing, and the boys farm work. The school was established in one of the buildings at Spring Hill in 1829, and moved in 1844 to a building constructed for it.

The Charity School of Kendal continued in operation until 1910. It was then leased to Summit County as a children’s home until 1924, when the property was sold for an allotment. The building was razed in 1926. The funds from the school became the Charity Rotch Foundation, which provides scholarships for students to this day. The Massillon Public Library has information about the school, as well as a student database available here.